When given the opportunity, most men love to collect. There are movie buffs, wine collectors, those who are into figurines, sporting memorabilia, collectors of old signs, car enthusiasts who scour garage sales for specific merchandise – the list goes on and on … which we’re very thankful for, or we would have trouble finding content for these pages.

Dr George Santoro AO may be described as a collector. However, what he collects may be a little harder to define. I was told by a mutual friend that I needed to see his typewriters, and they definitely lived up to expectation. George has some 16 magnificent typewriters, each one a classic model with intricate details you could study for hours.

Unlike many collections I see in this job, George’s typewriters are not stored together in the one place – some are in the workshop, others scattered throughout the house. In order to see them, George suggested we go for a walk.

It was on this little guided meander through his magnificent house that I started to realise George collects far more than just typewriters. There is a 1913 Philadelphia hand mower that took over a year to find all the pieces to get it working again. A magnificent Singer sewing table that can be folded into different shapes for various uses sits against a wall in another room. There are even convict handcuffs hanging from the wall next to an important barbed wire display.

We continue to wander and George explains each little piece and what had to be done to get it working again: a washing machine that is powered by water hammer, a clothes wringer, a resplendent gramophone, old lanterns, safety lights, countless pieces of old medical apparatus and scientific equipment, a hand-wound food processor from the 1850s, further small sewing machines and many, many more pieces… and this doesn’t account for the items he has donated to universities, museums and other institutions. If you were to take everything out and place it in one shop, you could put a ‘collectibles’ sign out the front and generate a lot of traffic.

It may appear a little disjointed but, to me, it makes perfect sense. Everything is hand-operated. Everything is mechanical by nature. Everything is made of individual parts in an era when they built to last or could be replaced if required to restore it to full working order.

It is clear that George has an obvious interest in these old mechanical pieces – he can tell you the history of each piece, where it fits into society and its importance at the time. Unquestionably he has an appreciation of items ‘built to last’ and perhaps there is a broader interest in engineering. But what makes George and his collection truly intriguing is his intimate understanding of how they keep his mind active and sane (though he likes to argue the last point!). Essentially, George is aware of what his collection does for him.

The fact of the matter is that Dr George Santoro AO is a medical professional of the highest order. He has been a general practitioner in Richmond, Victoria for 36 years and has held many positions as President, Chair, Treasurer and Board or Council member of the AMA Victoria, Federal AMA Council, is a Past President of Medical Benevolent Association of Victoria and far too many medical and university boards, as well as charitable groups and associations for me to list here.

He has a personal manner befitting of his many accolades. Behind the dry humour and slightly eccentric demeanour is someone who understands more about humans than most people will figure out in their lifetime. He doesn’t force that on anyone, but will happily discuss if asked.

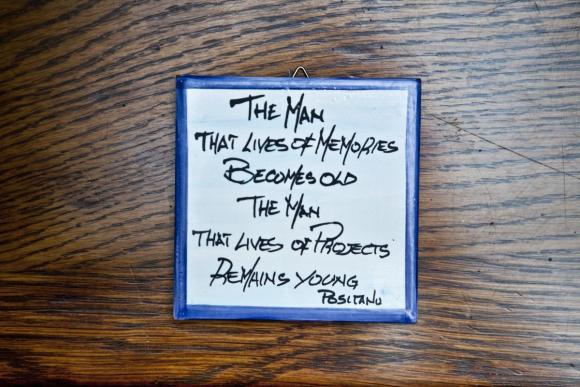

Amidst all of these amazing collectables, he fishes through a draw to pull out a decorative glazed clay square – no bigger than a drink coaster.

“I wouldn’t say this is my most important piece, but it is fundamental to life,” he says. “If anything, I suppose it should be the mission statement for your magazine.”

The plaque reads:

The man that lives of memories becomes old; the man that lives of projects remains young.

“The more men do, the less they become depressed. It’s a fairly simple concept,” he adds.

The inspiring part is that George clearly lives his own life with the same view: it’s not just a plaque for a doctor to show his patients in the hope of inspiring them.

He is an active member of a number of classic car clubs and still serves on many boards and associations. And he is always on the lookout for another piece for the collection.

“I’ve always been a collector,” he says. “We’ve been at this house for about 40 years so I suppose you would say that is when I really started to get a few bits and pieces because I suddenly had the space to hold them.”

While the typewriter collection is not overly extensive, he clearly has a soft spot for them.

“There is extraordinary detail with the old typewriters,” says George. “There is a reason why these things were made the way they were – some good and some bad, mind you – and understanding those reasons give you a better appreciation.

“The Helios was my first typewriter and a particularly interesting piece. It’s very compact, was built into a wooden carry case and was made for the First World War. The idea was that it would be small and transportable to be packed up and moved around easily during the war.”

There is a Yost typewriter, which is a particular favourite and the most complicated of George’s collection.

“The Yost is a non-shift typewriter, which means that there are two sets of keys; lower case and capitals. It’s called the ‘Grasshopper’ and falls under a category known as an ‘invisible’.”

When you see it in operation, you understand both terms immediately. The keys sit against the inside of a vertical cylinder which is lined with an ink pad; thereby requiring no ribbon. When you press a key, the long individual arm lifts out from the wall and pops through a small hole to press against the paper. It requires an exact mechanism movement to fit perfectly and the different length arms do indeed move and shape like the legs of a grasshopper. When the key goes through the hole, it hits the paper and prints the letter – however that paper is under a roller and cannot be seen – hence the ‘invisible’ tag.

As someone who is constantly deleting and retyping on a computer screen, I struggle to fathom how I could type an article on paper I couldn’t actually see…

“The amount of workmanship in designing this model is almost unimaginable,” says George. “Needless to say the absolute precision required means that they didn’t last very long – and they weren’t very practical – but they are still a wonderful example of typewriters in that particular era.”

It is also a reminder to the novice that not all typewriters had ink ribbons, words appearing in front of you or a little bell to signify you’d reached the end of the page.

George’s collection contains models known as Sidewhackers, Sliders and the Ball or Cylinder models – the latter of which is fascinating.

“The Helios has a Ball Mechanism where all the letters are embossed on the metal cylinder. When you hit the key, the cylinder rotates to its precise point and pushes against the ink to mark the paper. The extra feature with these is that you can lift off the cylinder and replace it with another that has the characters of a different alphabet – allowing you to write in a foreign language. It is a very flexible mechanism for something of that age.”

Again – extraordinary precision and logical thinking for a piece of machinery more than 100 years old. The detail with some of these models reminds me of a clock’s mechanism.

“I suppose some of them do,” says George thoughtfully. “Although, the clock is largely a decorative face with all the inner workings hidden behind – I think I prefer to see it all in front of me like you do with the typewriter.”

There are many collectables that you might consider to be old versions of items still in use today. The fact is that we will never see a new typewriter in mass production again and so it is a credit to the likes of George that he has not only saved them from landfill, but that he also restores them back to working order.

So does he have a list of items on the wish list?

“At my age it doesn’t work that way – you’d only end up frustrated. If I see an interesting little sewing machine or something I’ll consider it – then I enjoy arguing about the price with the person selling it – but at the end of the day, if you really want it then you have to pay for it. Some people think it’s a little silly to have all these bits and pieces, but I’ve never gambled in my life and don’t spend a lot of money on going out, so I think it’s purely a personal preference as to what we spend our money on. You know, you can spend a lot of money playing golf…” he adds with a wry smile.

Should anything need a little repair or maintenance, George can retreat to his workshop – an area he specifically had dug out around the foundations under the house.

It is a workshop that fits perfectly with George and his beautiful house. Items are neatly arranged and everything has a place, though there is still a sense of genuine useability and old-world charm. Because it was dug out from under the house, and therefore essentially surrounded by earth, it has a steady temperature and a wonderful sense of isolation from the rest of the house.

Work benches and assorted tools allow for repairs to be done – not that he is precious about undertaking all the work.

“I like to have a little tinker here and there, but I don’t hesitate to take it out and charm someone else into doing it,” he says smiling.

Even so, he still likes to understand what has gone wrong and work through how it may be rectified.

“Anything of this nature that gets the fingers and the brain working together has enormous benefit. When something is not working properly, you can problem solve your way around it to get it working again. If a part is broken, then you might be able to repair it, or you might be able to buy a replacement part – but you can physically see that it is broken. If you are dealing with an item that has an electronic supply or built-in microchips then it becomes far more difficult unless you are specifically trained.”

This understanding is something he practices personally and he is acutely aware of its value to anyone.

“I had a patient who was a typewriter mechanic and he had terminal cancer. He was at home and in the final stages of his life and I had the idea to ask if I could pay him to do up my machine. I went round to his house and he put a sheet on the dining table and placed the typewriter on top. Every night he took his medication, went to bed, then got up in the morning and set to work on the typewriter.

“I would drop by to see how he was going and he would show me the development with the machine but would not take any money – so I told him I wouldn’t be able to come by any more as I wasn’t comfortable with the situation. Even then, his family told me it was their job to worry about him, not mine, and that I should continue to let him work on it.

“I was later told that the last few days before he passed away were spent finishing the typewriter, and that he gave specific instructions that the family were not to take any money for it. I genuinely felt bad about it, but the family said it was the happiest they had seen him in those final stages – he got up every morning with a purpose and set himself goals to get through.”

While this tragic example does still show a positive result, George has seen many patients who he wishes had been able to apply that basic philosophy.

“If you’ve got a hobby – whatever it is – then you should just enjoy it. People can queue up and tell you something better to do, but it’s really none of their business. If I can offer anything through this article, then I would hope it is an encouragement for men to get out and do something – as that will lead to less depression.

“I’ve dealt with a lot of depressed men in my time as a doctor – many who served in wars. My practice was in Richmond and many of the men from war ended up in the area in tiny little boxes that were meant to be apartments with no space to do anything. Naturally, they all congregated to the local pubs and we developed a new era of alcoholics. It was horribly sad, but there was never any thought of educating them back then.

“I get so frustrated with all the people who talk or write books about reducing alcohol consumption because they approach it as an individual problem. I always said that you needed to sit down with them while they were still on the grog and discuss what else they are going to do – because the simple fact is that whenever an alcoholic gives up the drink, they suddenly have six hours in the day they never had before and they don’t know what to do with it. Inevitably, they pick up drinking again. I prefer to sit down with the individual and their family and work through what they are going to introduce back into their life before they give up the grog so they have something to do in those six hours later on.

“They might like to start helping at a place, or pick up drawing, or start a new hobby – it really doesn’t matter – but they need to have that activity ready to go.”

The man that lives of memories becomes old; the man that lives of projects remains young.

Well said.