It’s almost the end of the school year when we walk into the entrance of the Frank Dando Sports Academy. Unlike other private schools, you could be forgiven for missing it completely if you didn’t know what you were looking for.

Tucked away in a humble pocket in the south eastern suburbs of Melbourne, the school is hidden behind the home of the founder himself, Frank Dando. The only giveaway that this building is in fact a school is a sign that proudly states the details of a federal government grant.

Around the corner of the driveway, a bus packed full of noisy teenage boys can be seen – and heard. Kids are poking their heads out the window and calling not-so-helpful advice to one of their teachers, who is trying to pack the last piece of surfing equipment into the bus.

It seems like any other class going on any other excursion with any other teacher. But life at this school is not that transparent.

These boys started the year as some of the most troubled teens in Australia – some have behavioural issues such as attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or Asperger Syndrome; others are obese with low self-esteem; some have a healthy track record for being suspended or expelled from an assortment of schools; while others have fallen into the wrong side of the law.

No matter their background, all the lads have one thing in common: they have struggled both academically and socially in mainstream schools throughout Australia.

Seen as a ‘last resort’ by many worried parents, the Frank Dando Sports Academy challenges the conventional approach to education. For over 30 years Frank’s strict code of traditional maths and English, combined with a gruelling exercise regime, comes with a healthy dose of old-school discipline. In that time, he has taught and ‘straightened out’ more than 500 boys between the ages of 12 and 16.

“I wanted to start a special school for bright kids who crashed in the mainstream. At first, people couldn’t quite understand it – it seemed like an oxymoron,” Frank explains over a cup of tea in his home.

“It was a bit of a struggle to start off with, but these days I’m trying to repel them. There are 24 boys enrolled at the moment and we try to keep it at that number. We’ve had very few dissatisfied parents over the years … some have shifted down to Melbourne just to bring their kids here.”

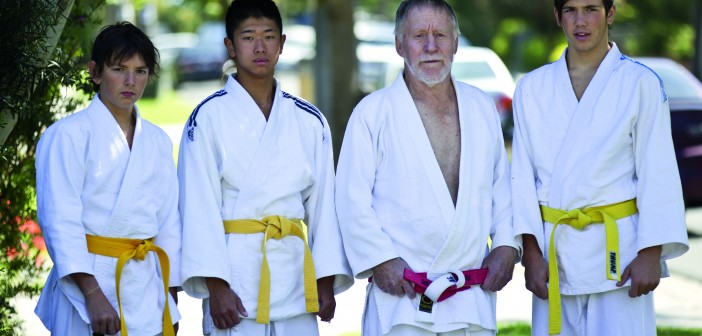

Sitting across the table from the seasoned judo veteran, you can see that Frank is not one to cross. He has been a teacher and a coach all of his life; and at 81 years of age he shows no signs of frailty, weakness or even retirement. Perhaps it is the result of a personal journey through the worlds of belligerent children and physical education, but more likely is the fact that this is all he has ever known since graduating from teacher’s college in 1950.

As Frank tells it, he was let loose on country schools as a 19-year-old graduate teacher and a “menace to the student population”, learning on the job and being brought up to scratch by the dreaded school inspectors. He then worked all over Melbourne, including schools in housing commission areas, which eventually sparked an interest in educating struggling children.

“It was in that kind of environment that you started to get the idea that teaching was a pretty serious business. Most of the kids were bloody hopeless so you did the best you could. There was a lot of pressure.”

Being a teacher didn’t stop Frank from challenging himself through higher education, and he can boast of studying Japanese language and sociology for an Honours degree. He also had the opportunity to visit Japan on multiple occasions, studying judo and “getting beaten up by experts”, which led Frank to explore the link between physical coordination and cognitive ability. It also paved the way for what would become 50 years of coaching judo as a sideline to his teaching responsibilities.

After returning to Australia in the 1970s, the seed for the Frank Dando Sports Academy was planted when he became a senior teacher at Clayton Tech (“back when we had technical schools”).

“I was the bloke in charge of social studies and English. Those were the days of corporal punishment and the staff knew that if they put a kid out of the class he was mine, and I’d strap him pretty hard. I used the strap pretty sparingly but there was plenty of theatre,” he recalls.

Leading up to the 1980s he could see that the ‘techs’ were going to shut down. As his speciality was in reading remediation “and probably still is”, Frank began a groundbreaking program. He researched the Doman Delacato technique, which is based on the theory that reading disability is caused by poor functionality from birth – this then led to further research for a Masters group at Monash University. Eventually he set up a program to help no less than 72 Year 6 students struggling with their academic workload.

“They would do one hour of maths, one hour of reading and one hour of physical education (mainly swimming at the local pool). Then they would go back to the school for their trade subjects. It worked perfectly.”

And the rest, as they say, is history.

School of hard knocks

The Frank Dando brand of education works on the theory of first having the boys enrolled experience success in physical education and sport. Quite simply, this builds the foundation for success in maths and English.

“The two things that affect a kid’s behaviour are the program itself and the teachers who are pushing it. Boys start to become reasonably objectionable when their hormones kick in – they become human again when they’re about 18 unfortunately,” he says.

“Most kids do two years here and switch in and out, so when the new group comes in, they face up to a peer group that is seasoned rather than all starting off from scratch. It’s a reasonably formidable group by most kid’s standards – but generally speaking, if they can take us then we can take them.”

From their first day, the kids realise that this is not your ordinary school. It resembles somewhat of a rabbit warren, with adjoining rooms and stairs leading off in every direction. A well-worn judo mat covers the floor of the main classroom-turned-gymnasium, which is decorated with Japanese sayings and photos of students past alongside the whiteboards.

After practicing intensive individual sports such as judo and boxing, it takes the boys five minutes to pull out the collapsible tables and chairs that are tucked away in a corner and set up for an English lesson on the mat. They then head to the beach in summer for swimming (or the local pool in winter), before returning for another lesson in maths.

“I’m a strong believer that early morning exercise makes kids more intuitive. If adolescent boys are sitting in a classroom for hours on end with no exercise, then it’s an invitation for trouble. We don’t have lunchtime here; they eat any time they like. We have to watch what they eat and any rubbish goes straight in the bin,” Frank laughs.

“They find themselves doing homework because this place is wacky enough to be doing anything. At the end of the year most will be steadily ploughing up and down the pool, swimming between 40 and 70 laps in an hour. Are they doing it cheerfully? I wouldn’t say that – but they do it. There’s some pressure from the older kids and the teachers as well, and their self-image builds up a bit.”

It probably helps that the teachers are also professionals in at least two sports. While the boys have a clear respect for their mentors, they are also fully aware that their teachers have more than enough power to make them toe the line if they start to act up.

“For instance, three of the boxing instructors have been pros. If a kid gets hit by one of them accidentally, he goes away to his mates and warns them that he’s not one to mess with. Judo is the same. We’ll hold a kid down and talk to the class while he’s trying to get out. That impresses the class. It transfers your instruction to all subjects.”

The teachers speak to the class with a firm tone – excuses are not tolerated, and the kids know it. All set work is carefully corrected with intensive individual instruction, homework is handed in at the same time each day and sloppy work is repeated after school. Detailed reports are sent to parents twice a year, and they regularly have the opportunity to provide feedback in the form of a Likert scale to describe how their son behaves at home.

“The point of this sort of stuff is that the kids are taught maths and English by the same people. The system is one-size-fits-all, but it’s also the result of skilful teaching. If the boys behave themselves and do what they’re told, they get plenty of positive reinforcement. If they start acting up, things start to get tough.

“We don’t threaten these kids or have any kind of discipline in place – it’s more of a process that pulls them into line.”

According to Frank, if the boys see some merit in the activities they complete, they’re more likely to settle down and get on with it. This is why there are four major excursions a year, all of which the boys have to write a report on when they return to school.

The first is a familiarisation camp in Daylesford, which Frank describes as the “first shake-down”. Here the staff can assess the boys’ behaviour to pull them into line and, by the end of the camp, they’ve gotten the message. Next is a three-night survival camp at Lederderg Gorge, which is a powerful learning experience as each boy has to take care of himself. They organise their packs, shelter, sleeping bags and look after their mates.

A downhill skiing camp at Mt Hotham is also on the agenda, which calls for a month’s preparation. On the same worn-out judo mat, they learn how to get in and out of skis and fall over properly without breaking any limbs.

Last but not least is the end-of-year surf training camp at Woolamai, which the boys work toward to receive their Surf Lifesaving medallion. The admission is simple: you have to swim 40 x 50m laps in an hour before you can even think about going on this camp.

“Teenage boys look for risk-taking activities. We understand this, but teach the skills in careful steps that remove most of the risk. Woolamai is scary stuff. The first thing they learn is how to do a rip swim and that is scary,” Frank says.

“During the year they learn how to do proper CPR, so by the end of it they’re experts at pulling people out of the water and looking after them. They walk away with a number of life skills.”

So what happens when it’s time for the boys to move on from the Frank Dando Sports Academy? According to the founder, they usually head back to a mainstream school for a second go, while some move into the tradie sector. There are even two or three who have gone on to become university graduates.

However, one thing is clear: there has never been a terror teenage boy that Frank couldn’t tame.

“They cope pretty well after they leave and there aren’t too many exceptions. We’re trying to turn out a self-respecting athletic boy, with reasonably good academic potential which is appropriate for his ambition and intelligence. That is the aim of this exercise: self-esteem and academic achievement through sport.”

Frank Dando Sports Academy

www.frankdando.com.au

A personal note from the publisher

A few months back I had a swap of personal trainer. Sam now has the task of motivating one of his most difficult clients.

Perhaps I should own up that there was a time when I thought personal trainers (PTs) were a bit of an overkill, until I signed up to tackle Kokoda a few years back and had to rediscover some of that old agility.

Like many ManSpace readers, I reckon I’ve signed up to a host of gyms over the past 40 years but never seen out the life of a single membership.

In the end, you generally give up as the discipline is not there; easily justified (to yourself) when you are putting in long hours running your own business.

However, a commitment to walk Kokoda meant I needed some added focus on my physical wellbeing, so I gave the PT deal a go and today I’m still sweating at a twice-weekly morning session.

You get to know a bit about your PT, being face-to-face with them for more than an hour a week, which means there is plenty of banter.

Sam told me he worked at a special school for boys, once he finished with me at the gym of a morning.

Then, watching 60 Minutes one evening, I realised that that was my Sam in a classroom shot on a story about the Frank Dando Sports Academy – an amazing learning institution for wayward lads.

Having watched the program, I then visited the Academy and you can’t help but be impressed with this unique form of schooling with boys who are off-the-rails at home or out of their comfort zone at a mainstream school.

They may have ADHD or some other issue that means they cannot settle and achieve in the classroom like most kids. They are also more likely to be a problem in the schoolyard and to society in general. At home it can also be an intolerable situation for parents.

How many other students’ lives such boys upset is difficult to quantify. What is known is that the mainstream schooling system just can’t cope with such out-of-control youth. The alteration of intensive sport with academic work ensures that any boys showing symptoms of ADHD are relaxed and attentive.

Speaking from first-hand experience, I wouldn’t want to be on the wrong side of Sam as an adolescent teenager either.

All jokes aside, he and the other teachers at Frank Dando Sports Academy have a tough job on their hands and they truly do an exceptional job getting these wayward teens back on the right track.

So why aren’t there more Frank Dando-type schools around the nation? That’s the thing a few politicians are asking themselves. But corrective education is not as easy as rolling out another McDonalds franchise; this isn’t cookie-cutter territory.