It is a fundamental truth: cars look best when polished, food looks best sliced with a sharp blade rather than being butchered with a blunt one, and cutting tools work best when sharpened to a mirror finish.

Unfortunately, cutting tools are often only rough ground on a high-speed grinder (or worse, but so common, never sharpened since being bought).

It is a mistake to think a blunt tool is safer. A tool that is too blunt to carve timber is sharp enough to do damage to you. A blunt tool requires more force, thereby increasing the risk of slips, mistakes and coming into contact with the working edge.

A sharp tool cuts with surprisingly little effort, produces a better result and is a pleasure to use. This is the case for a chisel, a circular saw blade, a drill bit or a kitchen knife. Paradoxically, sharpness is a safety feature.

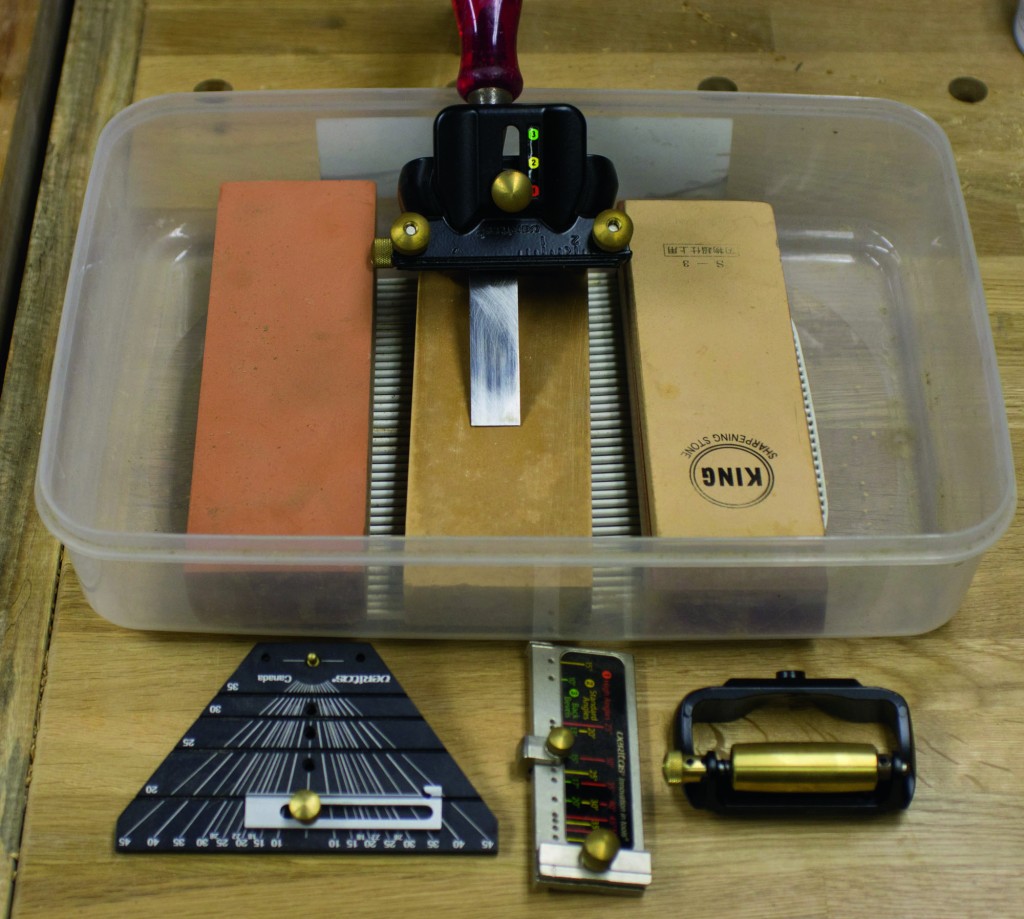

Many methods, jigs and abrasive systems are vying for a share of a fundamental requirement in tool use – a sharp edge. Available abrasive systems include (but are not limited to) sandpaper, grits, water stones, oil stones and diamond stones.

It might come as a bit of a surprise, but it really doesn’t matter which system you choose – assuming you use quality abrasives – or even whether you mix and match between them, so long as you work ‘through the grits’ from coarse to fine.

When sharpening, sanding or polishing something you start off with a particle size coarse enough to remove existing structures and scratches caused during initial manufacture or through frequent use.

The surface roughness will determine the correct grit to start with, and you keep working until the original marks are replaced with scratches from that first grit.

You then use the next higher grit to remove scratches caused by the previous one. It’s a case of ‘rinse and repeat’ through all the grades until the desired finish is achieved. As you work up through the grades, less and less material needs to be removed.

One stumbling block is the grading of abrasive materials. There are a range of system for depicting the abrasive properties of materials which all seem similar, but things don’t quite line up.

Is a 1000 grade water stone the same as P1000 (ISO system) sandpaper? And is that the same as 1000 mesh diamond stone, or 1000 grit sandpaper using the CAMI grading system? The answers are sort of, no and no.

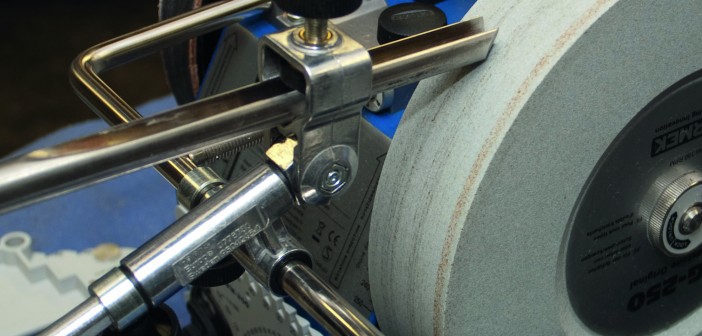

Abrasive materials are made up of small particles that are harder than the substance you want to abrade. They can be in the form of a powder that has some oil added and is used on a flat surface, or combined with a wax and added to a felt wheel. They can be secured in a permanent base or glued to a paper surface that releases particles as it wears. They can be in a soft matrix and formed into a flat slab or slow-spinning wheel.

The solution to all this is to concentrate on the micron size of the abrasive particles – the full particle size for a loose particle surface, or the exposed particle size for fixed surfaces (diamond stones typically have two-thirds of the diamond embedded, a fact that most grit comparison graphs omit). Then you can move consistently from larger to smaller micron sizes.

Choose an abrasive system that works for you. However, opting for the cheapest doesn’t always save money, let alone achieve the desired effect. It takes only one rogue particle to score the surface, thereby wrecking the finish. If you do need to intermingle different abrasive systems, evaluate the micron size of the abrasive particles first to ensure you don’t make the mistake of moving from a finer abrasive to a coarser one.

A MATTER OF BONDING

Two common methods are used for bonding abrasives to the backing material: open coat and closed coat.

The first involves a lower particle density, so the entire particle can dig deep into the work to remove material faster and reduce the likelihood of clogging by waste. The working size of the particles is closer to their actual size.

The second pattern is when particles are tightly packed. With a smaller gap between particles, the bite is not so deep, resulting in a finer finish (or finer scratch pattern), and the working size of the particles is much less than the actual size. These materials tend to need some form of lubrication because of heat build-up.

Abrasive particle sizing is subject to many systems, including CAMI/UAMA (Coated Abrasives Manufacturers Institute and Unified Abrasives Manufacturers Institute), FEPA (Federation of European Producers of Abrasives), USS (United States Standard Sieve) and JIS (Japanese International Standards).

Grit size in these systems is an arbitrary designation with no relevance to physical dimensions. The only real way of comparing abrasives is to focus on the micron size of abrasive particles.

The concept of ‘mesh’ originated in a sorting method for determining the size of particles by passing them through a number of sieves with decreasing hole sizes until they could go no further. These days particle grading is achieved by more precise technological methods, but the original unit remains.