If you ever liked a game of hide and seek when you were younger – and you’re pretty handy with a GPS – then you might want to try the high tech treasure hunt that is geocaching. Roy Mercer speaks to Dimi Kyriakou about discovering the path to his passion.

It’s really thanks to a bunch of old uninformed potato farmers (and a well-established career in electronics and engineering) that Roy Mercer arguably takes the title of the geocaching pioneer of Western Australia.

Geo-what, I hear you ask?

Before I tell you about the marvellous character that is Roy, I better explain the gadgets that grace the pages of this article. Yes, that’s an ‘unexploded bomb’ that Roy’s leaning against – but, like many things in life, it should not be taken at face value. It may have been a length of PVC drain pipe in its former life, but now it spends its days as a surprise geocache.

Geocaching is a real-world, outdoor treasure hunting game that uses GPS-enabled devices. Participants navigate to a specific set of GPS coordinates and then attempt to find the geocache (usually a container, also referred to as a ‘cache’) at that location. It can be anything, hidden anywhere – the fun is in using your own intuitiveness to locate the cache, open it (sometimes there’s a trick to it) and sign the logbook, then return it to its original location and share your experience with other geocaching fanatics.

Sounds simple enough, right?

Well, despite the fact that there are over two million active caches worldwide and more than six million geocachers looking for them, Roy’s road to the hobby was not exactly direct, nor was it planned. After growing up in the United Kingdom in the middle of the Second World War, Roy and his family swapped the cold streets of London for the scorching desert of central Western Australia in the name of the White Australia Policy and the famous ‘Ten-Pound Pom’ scheme.

After struggling to master the local education system and find a career that played to Roy’s strengths – he was always fascinated with technology and had strong visual and drawing skills – he eventually enrolled in night school to study electronics. Balancing his studies with a job at the local hospital taking care of research animals, Roy then had the opportunity to take up a position at the University of Western Australia as an animal house technician.

“That was where my life really began,” Roy recalls. “The animal house was run by the Department of Physiology, but was adjacent to the Department of Pharmacology who were a great user of rats. My job required me to regularly deliver cages of them to the labs.

“One day I came in to find a gaggle of the best brains in pharmacology huddled around the latest piece of technology: a Tektronix CRO. They all had twiddled every knob and completely lost the trace. I sidled up to the back of the crowd and slowly worked my way to the front to admire this wonder. And with a practiced hand pressed the beam finder, set the trigger to auto and adjusted the focus and vertical gain to produce a sharp steady trace.”

Needless to say Roy had captured the attention of these “white coated geniuses” and soon became the assistant technician for the department, where he repaired and built lab equipment to run more efficiently for research and teaching.

“I made bits of whatever gear was needed. This brought me into contact with the uni’s workshops: a veritable paradise of machinery. I was taken under many wings and learned many new skills,” he says.

After being headhunted by the West Australian Institute of Technology (now Curtin University) he was then able to design his own workshop with practically unlimited funds, until budget cuts saw him “sold off” to the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department to work as a senior technical officer.

“My time at engineering was some of the best years. The work was very interesting and as it turned out the best training for a cache maker,” he explains.

Roy eventually retired to a 17 hectare farm in Denmark on the south coast of Western Australia with his wife – and thus the next chapter of his life came into play.

Finding the world of geocaching

Roy’s place of retirement offered picturesque views alongside wonderful soil, two permanent dams, a couple of orchards and excellent grazing paddocks – except in reality, “they weren’t all that excellent”. The potato farmers of the 1950s were a little heavy handed on their insecticides of choice, the now-banned substances of DDT and Deldrin, so the contamination was far above the acceptable limits and would make grazing cattle a problem.

“Then we heard of a bacteriological treatment that was supposed to fix the problem: clever little bugs that would eat up all the contaminants and beg for more! We contacted the local Agricultural Department and they were keen to experiment. So we purchased some of the stuff and sprayed it around. The Ag officer and I did soil tests before and after,” Roy says.

“To do the tests I needed to be able to locate – and relocate – a set of random sites in a four hectare paddock. The obvious solution was to get a handheld GPS receiver and let the satellites do the finding. A quick session on e-Bay turned up a suitable unit and within a week I was reading through the user manual and getting familiar with the operation.

“It all made perfect sense, but there was one file in the data structure I didn’t recognise: ‘geocaches’. I looked up the website and it looked like some kind of treasure hunt. Not much help for finding soil sample sites, but I was curious. After we’d done the first spray and were waiting for the bugs to do their thing, I looked at it again.”

He registered his details as a geocacher and decided to test it out during a trip to the nearby town of Albany. After entering his location and choosing from a list of available caches nearby, Roy followed the coordinates and navigated his way to the treasure, all the while being updated on the remaining distance and direction.

“I was starting to get a bit curious as to what I would find. Despite my original blasé approach I was getting a bit excited,” he says.

“The path ended in a little glade with a wooden bench and the most splendid view of King George Sound with Albany nestled comfortably between its two embracing hills. I sat down on the bench and looked about. Nothing there… until I saw some rubbish just visible stuffed under a bush behind the bench. I thought I’d better do the right thing and remove it.

“But it wasn’t litter. It was a grey plastic bag containing a plastic clip-top box with ‘Official Geocache – Do Not Remove’ written on the top. Inside was a notebook, a pencil and a collection of little trinkets. Despite myself I was enchanted. Someone had gone to the trouble of setting up this little treat just for me – or so it felt. And it brought me to a delightful spot I would never have seen otherwise. Geocaching then became my favourite hobby… and by the way, the little bugs did the job and we now graze happy cows on our farm!”

Making and hiding geocaches

As Roy explains, there are two basic types of geocachers: hiders and finders. All hiders are also finders, but not all finders are hiders, as many don’t have the opportunity, ability or inclination to go through the sometimes tedious process of hiding and registering caches.

While Roy’s first taste of geocaching was in a finder’s role, he is also a ‘maker’ of caches – which is effectively a subset of hiders.

“We’re those who are tired of the old ‘box under the bush’ approach and are applying the creative juices to come up with new and interesting ways to present a cache. I actually get more pleasure from making caches than I do from finding them,” he says.

“If I think of an idea, I have to make it to see if it works. My basic rule is to build it strong and keep it simple.”

Roy’s signature style often draws on two particular characteristics: his motto that finding the cache is just the beginning of the fun, as well as his decades of experience in engineering.

“I prefer to make ‘camos’ – camouflaged caches hidden in plain view but disguised to conceal. I think it’s more of a buzz to suddenly realise you’ve been staring at the cache and not seeing it, and then – there it is!”

Roy’s very first hide was a camo, which he believes was the first in the southwest. The location of choice was an abandoned and disconnected meter box on a pole at the top of the lookout of Mt Shadforth, which is easily accessible by car. Roy put his skills to good use to construct a junction box out of similarly old sheet metal and then stuck it on the back of the meter box with powerful magnets. But, sadly, the local council decided to remove the pole, meter box and cache in one go.

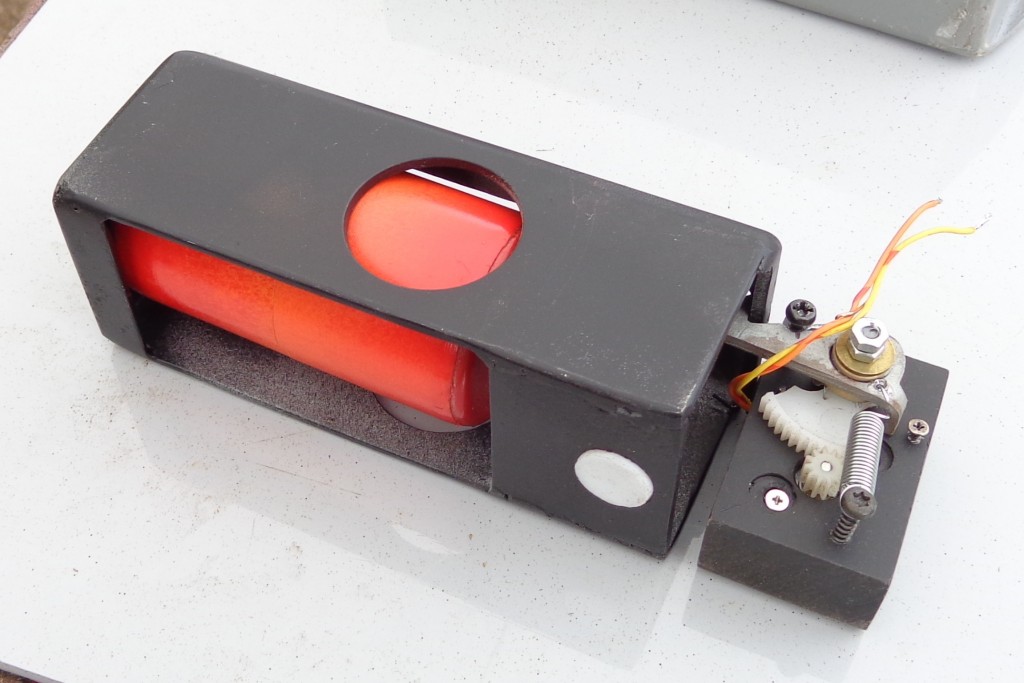

While camouflage is a common trend in Roy’s designs, they are often also mechanical. Another time he built a release mechanism on a cache that would be mounted in an alcove on a former railway bridge that spans the mouth of Denmark River. It can only be activated by pressing the two terminals on top of a 9V battery against two matching contacts on the box, which would allow access to a small canister containing the log book.

While clever enough in theory, Roy discovered first hand that building elaborate interactive electro-mechanical caches means you will forever be going back to fix them.

“But every time I do, I consider it as an instruction in design. After much experimentation I ended up using a small 5V motor scavenged from an old floppy disc drive to revolve a quadrant that operated the catch release. It worked a treat and has been one of my most reliable constructions.”

If not a mechanical failure, the ignorance of council representatives or even members of the general public can mean that caches can be damaged or, as demonstrated earlier, removed completely. This is why it is often essential to gain the permission of the council or owner of the land where the cache is located.

Roy has built up a good relationship with the Shire of Denmark Office, which has since agreed that it is a good way to boost visitor numbers to the tourism-dependent town. His caches are very well known among the geocaching community and some are considered to be the most elaborate in the state, which brings travellers not only from Perth but also the eastern states of Australia; even as far as Germany.

“Denmark is now officially geocache-friendly and will strive to assist and support quality caches. It is a small town and there are only a few geocachers here. In Albany, there are many excellent and very creative hiders and keen finders. A spirit of friendly co-operation exists between all of us.”

As with any game, there are some rules to abide by. You must return the cache to its original location and if you take something, it must be replaced with another item of equal or greater value. Another rule stipulates that you must always sign the logbook – and while you may think it will be found within the cache itself, you might also end up in a library if Roy is behind the contraption.

“Libraries need to justify their existence and budget like everyone else nowadays, and it’s bodies through the door that count. When I nervously did my presentation to a local librarian she said, ‘What a marvellous idea!’ and put the staff to work finding a suitable Dewey Decimal location,” he laughs.

“I now have a book listed in the library online catalogue under ‘Australian Treasure Trove’ and geocachers who find it and log their visit can truthfully say they have some of their writings on the shelves of a public library in Western Australia.”

Join the geocaching brigade

Roy heartily recommends geocaching as a hobby to ManSpace readers, as it combines a bit of technology with a bit of bushcraft, a bit of thinking and a good bit of physical exercise.

“If there are any retired engineering types with well-equipped workshops looking for a creative challenge, there are still a lot of innovative caches waiting to be invented,” Roy says.

“I personally get plenty for all my work: the pride of achievement; the blushing glow of smug self satisfaction when someone writes flattering things in the logs; the knowledge that I’m helping my community by encouraging much-needed tourism. And I get other benefits. After retirement from 40 years of making weird and wonderful gear for teaching and research, the sudden extinguishing of the inventive and creative buzz was a jolt. Those mental gears just want to keep on spinning. Creativity stimulates and energises the brain and it’s my way of holding off all those fearsome threats of ‘old age’. Keep your brain active and young, keep busy, and the body just has to tag along!”

You could say that Roy Mercer’s path to geocaching was much like the game itself – a few twists and turns here and there, but the end result was far beyond any initial expectations.

Are you clever enough to find and open one of Roy’s geocaches? He goes under the username ‘roymerc’. To find out more, visit www.geocaching.com.