As a handful of intrepid motorists prepare to drive their vintage cars across two continents, Paul Hickman tells Jacob Harris about the series of events that led him to be a part of one of the world’s most historic endurance rallies.

A superstitious person might say it is fate that will lead Paul Hickman to drive from China to France in a Bristol 403. Certainly, if it wasn’t for a series of serendipitous events it’s unlikely Paul would be competing in what is arguably the world’s greatest motoring adventure: the Peking to Paris rally.

Paul, who by day is CEO of ground engineering firm Mainmark, has long had an interest in restoring vintage Bristols (the 403 he’s racing was built between 1953 and 1955) but this is not just a story about one man’s love of motoring – it’s also a story about a chance encounter that led to a rather unlikely relationship.

“Late one rainy night my wife and I were walking down a street in Sydney’s Newtown after seeing a movie. I heard a sound emanating from a dark doorway and said to my wife ‘bugger me, that’s a Mongolian throat singer’,” Paul says.

Paul had become enamoured with Mongolian throat singing 25 years earlier when he saw a program on the obscure artform in far north Queensland. So upon hearing the sound unexpectedly on an inner-Sydney street, he doubled back to investigate.

“I went back and found an amazing musician so I stood there and listened to his music.

“ Two weeks later we were walking down the same street and came across him again – on the same dark corner playing away.”

Not long after this was Paul’s 58th birthday. To celebrate, his wife organised an impromptu get-together with live music and friends. And who should arrive but the mysterious throat singer, Bukhu.

“He’d been out here for two years. He had come out with his wife, Chimka, to study English but she had to return to Mongolia to try and sort out her visa. Bukhu was busking on the street and doing what he could to earn a quid while living on a settee in Southerland. I just wanted to help the guy – he was such an awesome musician. Everyone who was playing music that night deferred to him. It turned out he was actually a lecturer in folk music at Ulaanbaatar University (Mongolia),” Paul says.

Paul helped Bukhu organise Chimka’s return and – due to their accommodation falling through at the last minute – also ended up offering them a place to stay.

Paul and his wife agreed the pair could stay in their studio for 11 weeks. But before long, a strong bond was formed between the two couples (Paul says he loves them dearly – as though they’re his adopted children) and nearly six years later Bukhu and Chimka have only just moved out to buy their first unit.

“Chimka, who we hadn’t met before she moved into the studio, turned out to be absolutely brilliant. We employed her at Mainmark. She started in marketing and she’s now second in charge of accounts. She’s actually just been approved for a visa for people with extreme talent. Australia only lets in about 40 (often world renowned) people a year on these visas so it’s a pretty impressive feat.”

As a result of the relationship, Paul became more and more interested in Mongolia and was also doing an increasing amount of work on his two Bristols. He felt compelled to do something really obscure so when Bukhu mentioned he had once seen a bunch of people in strange cars driving through Mongolia, Paul did some research and discovered the Peking to Paris.

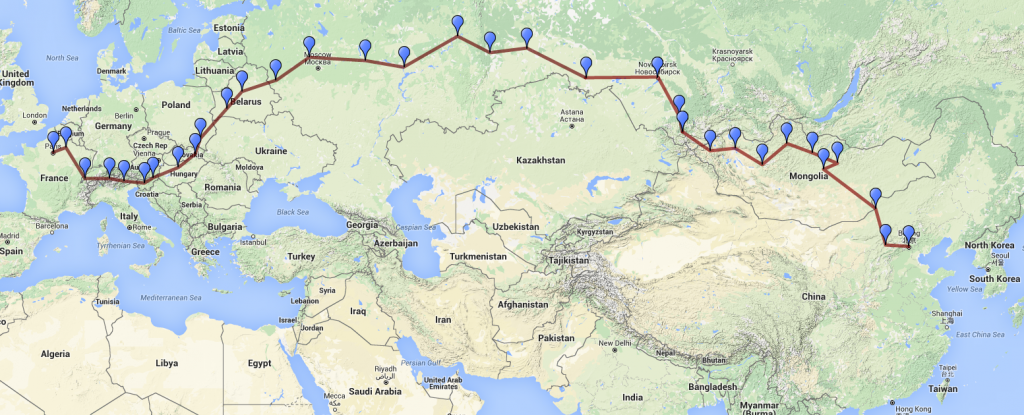

The race first began in 1907 as an open challenge to motorists to drive unassisted, through remote, often unmapped countryside from Peking (now Beijing) to Paris, the reward being a magnum of Mumm champagne.

The 2016 race will be only the 6th time the event has taken place as the formation of the USSR prevented the race being held again until the 90s. The rules stipulate cars that compete in the challenge must have been built either pre 1941 for the vintageant category or pre 1975 for the classic category.

At first Paul didn’t even know what kind of car he wanted, though it does seem somewhat unlikely he would have ended up with anything other than a Bristol. Paul knew they were fairly rugged – in the 50s a lot of Bristols were used on farms in Victoria because they could belt up and down the paddocks and unpaved roads – and that as yet, a Bristol had not competed in the Peking to Paris.

This is especially significant for Paul because after establishing his love for the British marques he discovered he actually had a family connection to the Bristol company.

“My grandfather was involved with the companies that preceded the Bristol Aircraft Company. Back in 1896 there was a company called Straker-Squire which became Cosmos which became Bristol Aircraft Company which in turn became Bristol. I didn’t realise there was such a tie up between my family and the Bristol car until I actually bought one and started researching things. Now the Rolls Royce Historical Association is doing a retrospective on the family – which is a result of me asking questions.”

Indeed, Bristols seem to pervade many aspects of Paul’s life. His co-pilot for the rally, long-time friend and North Riding (Yorkshire) tribesman Sebastian Gross is a recognised restorer of Bristols. So when it came time to locate a car to do-up for the rally, Sebastian was a key member of the team.

“The car was found in a shed in Dungog, NSW. According to the rego sticker, the last time it had been on the road was 1981. It was in bits and pieces when we found it but we actually managed to get the engine started – I think it was running on two cylinders but it was going!

“It was full of rat and possum crap and god knows what else – 30 years of rubbish. We decided to rebuild the whole car so we actually stripped it completely down and rebuilt it.

“I counted 1000 hours I spent stripping paint and polishing and cleaning things – I’m glad it’s over,” Paul says.

With all that time and effort put in – and the stunning result – you might think Paul would be feeling a little apprehensive about subjecting his precious ‘Silvia’ to the inevitable bumps, scratches and worse that will come from traversing such wild country but the Englishman maintains that he believes possessions should be used and not merely looked at – no matter their inherent worth.

“All I want to do is get to the other end. We’re not famous rally drivers or accomplished racing drivers of any sort. We realise that some people in classic motoring circles consider this the motoring equivalent of sailing around the horn of Africa on a yacht. In 2013 a woman died and several people were hospitalised. It’s not all doom and gloom but you do have to be careful – so I’ll be happy just to get to the other end.”

The Gobi Desert in Mongolia will present some of the most challenging terrain. There are no real roads (a road that existed last year won’t necessarily be there this year) for about four days of the journey so drivers are working completely off GPS.

“You’ve got to make your own way – follow the telegraph poles if you get lost, they’ve got to go somewhere,” Paul laughs.

Paul’s wife and Mongolian friends – as well as an old work colleague in yet another Bristol – will be following the intrepid pair through Mongolia for two weeks before meeting again in Paris.

“I’ve got 60 people meeting me in Paris. We’ve hired a nightclub for a party. It’ll be brilliant.”

Paul and Sebastian will be using their adventure as a way to raise money for the Bright Light Organisation: a Mongolian charity that helps disadvantaged women living in shanty towns or slums by teaching them life skills.