If you own a vintage car, you’ll know that although it’s an incredibly rewarding pastime, one of the major hardships is finding and rebuilding parts that are no longer available. Imagine if you could just ‘scan’ the part you need, and print it out in a matter of hours.

Yes that’s right. Print it out.

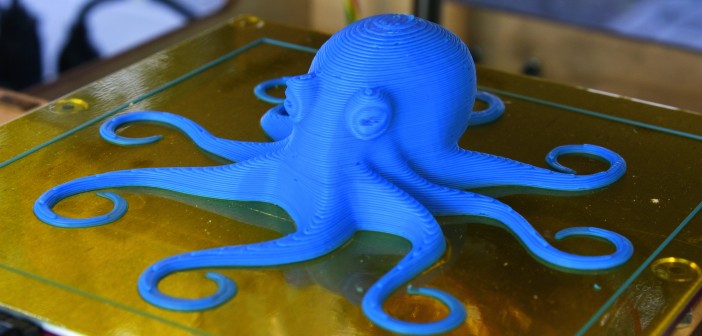

That’s the power of 3D printing. The possibilities are almost limitless. There are blokes out there in their garages printing out everything from broken door knobs, to their own fishing lures and model cars.

It sounds like a hobby that would take the brain of a rocket scientist and the wallet of Bill Gates but, the truth is, 3D printing is not very complicated and can be relatively affordable. All it takes is a little machine, some plastic and a bit of technical knowhow.

As with any type of manufacturing, there are 3D printers on a massive scale that cost millions of dollars. There are printing ‘bureaus’ situated in Australia and across the globe that take a customer’s design and turn it into a physical object. These companies work across a range of industries, and print everything from model buildings for architectural firms, to customised artificial hips for surgery and product prototypes for engineers and budding inventors.

Surprisingly, this technology isn’t a new development – an early version using stereolithography (SLA) has been available since around 1974, which involves a bed of liquid that is hardened using a laser, working in 2D layers that are stacked on top of each other to create a 3D form. However, it is only in the last few years that the technology has become more refined and printers have become accessible to the average Joe. You can get a printer for your home that is not much bigger than a microwave and costs just over $2000.

The product that really kickstarted the domestic 3D printing movement was the RepRap, developed at Bath University in the UK. The developers set out not just to build a machine that could print in 3D, but also a device that could print itself. It could reproduce around 70-80% of its mechanical and structural parts (excluding some of the metals, circuit boards and electronics) and is not just a great way of printing in 3D, but also an incredibly powerful idea within the manufacturing space.

From that project came a range of accessible machines such as the RapMan 3.1, the BFB 3000 Plus and also the MakerBot – a smaller timber-encased machine that is very popular in the US.

ManSpace Magazine paid a visit to Origin Systems, a company based in Melbourne who distributes the RapMan 3.1 and the slightly more advanced BFB 3000 Plus.

The RapMan is slightly cheaper, and almost seems like it is designed with the handyman or hobbyist in mind as it requires you to build the printer from scratch. It comes flat packed, so if you’re a guy who loves making and fixing things, there’s a pretty good chance the RapMan 3.1 is for you. It can take a while to assemble – between 12 and 24 hours, but if you see yourself as a bit of a tinkerer, there has to be something incredibly satisfying about printing an object you have designed with a machine you’ve built yourself (if you follow my logic…).

The BFB 3000 Plus comes pre-assembled, has a slightly larger print area than the Rapman 3.1 and has the option of a twin head unit for support material and a triple head version for experimental projects.

Origin Systems director Chris Peters explained a bit about the techy side of things to us.

“These two machines are fuse deposited material (FDM) machines – so they are basically a glorified glue gun. You have a very small computer numerical control (CNC) controlled nozzle which takes the plastic, melts it and then applies it to the surface or the material on which you’re printing. Then layer by layer the machine builds your part up.”

The plastic in question is acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (or ABS to you and me), a common engineering-grade plastic – the same material used to make Lego. It comes as a 3mm filament on rolls much like general cabling, and is available in six different colours.

Chris says that ABS is also a surprisingly affordable material and the cost of printing is primarily determined by the item’s weight.

“ABS ranges from around $50-100 a kilogram, depending where you buy it, so if you were to make an item which weighs around 200g, you could print it for under $20, whereas if you were to go to a bureau, that could cost you up to $500.” He does however, point out that prints from a bureau tend to have a much better quality.

The printing itself is actually the simplest part of the process – all you have to do is leave the machine running, as you would with your computer’s printer. The most complicated aspect is the initial creation process.

If you want to realise your own design and form an object completely from scratch, you need to have a knowledge of using computer-aided design (CAD), which involves using software to design your object in 3D before you can send the file to the printer.

However, if you already have an item you want to replicate, you can use a 3D scanner which you simply run along an item, calculating the object’s parameters and measurements. This can then be imported into CAD software before printing.

Sydney-based Jonathan Wong is a 3D prototype designer and hobbyist who owns a Rapman 3.1. He says he has heavily modified it with parts it printed for itself, and because of its small size and quietness, he can simply sit it next to his PC and “the wife doesn’t mind too much!”

Jonathan has a background in 3D modelling and animation, so previous CAD experience helped him produce the parts he needed, however he notes that there are an increasing amount of simple options for those new to 3D design such as Google Sketchup and a website called thingiverse.com which lets users download completed 3D models and print them.

“Being able to create custom 3D designs is possibly the biggest obstacle to finding a 3D printer in every home; the learning curve is much steeper than typing up a Word document and hitting ‘print’,” he says. He uses his machine to create engineering prototypes for himself and his clients and he also uses it to print artwork for general display – he even has three pieces currently on display at the Inspiration Centre in Amsterdam.

“About five years ago I wanted to physically test a design for a door latch mechanism that I had conjured up on the computer,” he says.

“The design was too complex to make with hand tools, so I used a local prototyping firm. The astonishment of holding my digital design in my own hands was enough to get me curious about owning my own machine.

“For complex designs, 3D printing is the only way to achieve fine details that would be impossible using traditional subtractive method such as woodworking or CNC machines. It’s also a much cleaner and quieter process with a very large degree of automation; a properly set up machine can be fed a file and it will spit out a model with just the press of a button.”

Jonathan carries real passion for the technology and he advises anybody considering taking up 3D printing to just dive head first into it.

“3D printing is definitely a learning curve and a very hands-on experience, and with the support of the many community forums available you’ll be up and running in no time. Also, there is a correlation between machine price and print quality; cheaper machines will teach you a lot, but you may run into their limitations sooner rather than later. Most importantly, have a clear goal of what you want to achieve with the printer, and don’t lose sight of that goal. It’s very easy to become obsessed with making the 3D printer evolve itself.”

Some schools of thought say that in ten years there will be a 3D printer in every home. To many of us, this will inevitably seem like a farfetched statement. Then again, a lot of people didn’t believe Bill Gates when he said that there would be a computer in every home, but it happened, and nearly every home has a printer to go with it. 15 years ago many of us wouldn’t have even dreamed of having a desktop printer in the home, but as they became more affordable, widespread and society became more accepting and familiar with the technology, the popularity grew. So who knows, maybe the same will happen for 3D printers.

That isn’t to say that 3D printing will necessarily sit next to the family computer, in fact, it’s more likely to sit proudly in the man space. 3D printing is really geared towards the bloke who loves tinkering around and making stuff; just as you’d struggle to find a hobbyist or woodworker without a mill or lathe in the garage, maybe the more tech-savvy, next generation of handymen wouldn’t dream of having a shed without a 3D printer.