Like many readers of this magazine, we at the Institute of Backyard Studies (IBYS) are big tool collectors. Most Sunday mornings you’ll find us out at garage sales, swap meets or the trash’n’treasure, casting expert eyes over piles of rubbish and junk in a search for that elusive little beauty. A Stanley plough plane from 1923 perhaps … or maybe a Wilkinson folding drawknife is just sitting there, waiting for our loving touch. You live in constant hope of that big find and some days are good.

Mostly the tools we seek are British or American, from the glory days before cheap Chinese imports swamped the market. There are even some brilliant Australian tools out there from our own brief period of tool-making greatness. But there’s one name that the serious tool collector is drawn to, a name full of mystery and intrigue … and that name is Henry Hoke.

Henry Hoke and the extraordinary Hoke’s Tool Company was a classic tale of struggling against the odds, the plucky little battler with a burning passion to see his brilliant ideas turned into reality and to see the resourceful Australian genius for invention take its rightful place in the world.

Henry Hoke was born sometime early last century in Hoke’s Bluff, a windy little town on the railway line heading north. There’s nothing there now – just a few ruined buildings that have mostly blown away. The town itself has even blown off most maps. But in its heyday, the Bluff was a prosperous town, where Henry’s father, Dr Silas Hoke, ran Willing’s Pharmacy. The rather sinister Silas Hoke had invented a famous patent medicine called Willing’s Suspension of Disbelief, which made him a considerable fortune.

Henry’s mother Beryl was a celebrated marmalade maker and a highly skilled blacksmith. She was the Head Hammerwoman of the local Ladies Blacksmithing League – an organisation frequently described as being a cross between the Country Women’s Association and the Hell’s Angels. Her skill at tempering spring steel was legendary and Henry must have learned much from her.

Henry left home early and worked in a wide range of occupations and always showed a brilliant gift for invention. A stint as a fencer resulted in Henry coming up with a range of pre-dug fence holes, which all agreed was a massive time saving device. Or a period as a young mechanic at Short and Curly’s Garage gave birth to the now universal Chuckle Valves and Giggle Pins that are essential to the work of every mechanic. And, of course, his widely used K9P, the spray lubricant and food additive which became a standard in every toolbox across the nation.

After a few years knocking around the bush, Henry took off overseas to work in the merchant marine, where his Patent Waterproof Shoreline met with great acclaim and his Ship’s Foghorn Tuning Pipe (which he described as being able to tune the foghorn to penetrate the “fog of the human mind”) became an international nautical standard. And these are just a drop in the bucket of the prodigious inventive life output.

So why did he not become a massively rich and widely known Australian inventor whose image might be found on the back of a 30 cent coin?

Perhaps it was his unfortunate innocence about financial matters or that he believed in the egalitarian tradition of freely available knowledge and ideas. We’ll never know for sure because he wrote very little, preferring to let his tools do the talking. Between stints working around the country or overseas, Henry would return to Hoke’s Bluff, where he set up the Hoke’s Tool Company, a corporate vehicle for more of his colossal inventive output which only seemed to increase as a result of past failures.

Henry could have become bitter at his constant knockbacks but no, he kept on attempting bigger and more ambitious schemes. His clockwork car, for instance, was extraordinarily fast (initially) and it was bought out by a certain large US car company for a pitiful amount of money.

When petrol prices hit $5 a litre, then we can expect a sudden “rediscovery” of the clockwork car. In the meantime all we have for proof is the Hoke’s Giant Windup Key to his old clockwork ute… If there was one great endeavour that described the great man’s work, it was his last and most ambitious project – the Random Excuse Generator.

Fuelled by the strange penetrative powers of Super Refined Bulldust, the REG (as it was known) was able to exploit the mind-boggling concept of turning matter into ideas. By turning the Bulldust into high pressure Gasified Concepts, the Generator was capable of making highly credible excuses in a range from personal to domestic right through to International Diplomacy.

For this work, Henry Hoke should have won the Nobel Prize for Physics, at least. But tragically, overexposure to Super-Refined Bulldust led to an apparently fatal attack of Procrastinator’s Syndrome. Towards the end it was hard to even get out of bed – he found his mind always had a perfect excuse for not getting up.

His passing was a tragedy and we in the Institute of Backyard Studies have dedicated many years of work to hauling this great Australian’s shining reputation back into the spotlight he so richly deserves. We’ve tracked down many of his tools or at least the containers they came in and have published a book of his life and tools.

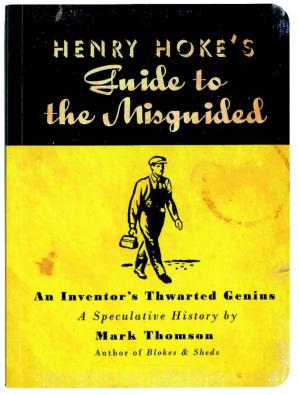

This book, entitled Henry Hoke’s Guide to the Misguided, gives the full story as far as we know it.

So the next time you use a Smoke Hammer on your engine, or you swallow a couple of Dehydrated Water Pills on a hot day or use a Wooden Magnet to clean the sawdust in your shed, think of Henry Hoke and wonder about what it all means. We’ve got no idea.

Further information about the Institute of Backyard Studies, its dubious products and books and even about joining as an ‘Associate’, can be found on the website at www.ibys.org