Damian Kringas reflects on the life of Aussie stuntman Dale Buggins…

A few years back I wrote a biography of Australian daredevil Dale Buggins. I wrote it because there was no book about his life, and I felt that wasn’t a fitting tribute to someone I thought deserved more. I’d seen Dale at the showground in Sydney and in my mind, he was a legend. But the life of Dale Buggins had two distinctly different parts. One was how a stunt rider from country New South Wales captured the imagination of millions of people both in Australia and overseas. The other was the tragedy that saw him take his own life at the age of 20.

I have this picture in my head of a woman hanging washing on a clothesline. In the background the sound of a two-stroke motorbike is getting louder, until bang, it’s flying over the top. The annoyed woman yells out, “Dale,” but it’s no good. Dale’s landed and racing down the back paddock.

It may or may not have happened but one thing is certain: Dale’s childhood up on a rural property just outside Wyong, northern NSW, fostered his obsession with riding and jumping trail bikes. This obsession led him to the Newcastle International Motordrome on May 28 1978.

The huge crowd was hushed. Buggins was heading toward the ramp at what seemed to be an endless line of cars at nearly 100mph. He hit the ramp and soared about 40ft into the air. A woman fainted nearby. Buggins’ mother turned away and the commentator became speechless.

In front of a 10,000 strong crowd, Buggins at the age of 17 jumped 25 cars, clearing a distance of 42.25m. It was a new world record, but not just any record. He’d broken American legend Evel Knievel’s record. He’d built himself up slowly; 13 cars, then two aeroplanes – but this set him up for the big time. This jump launched Buggins into a career, following his dream of performing as a daredevil on an international stage.

Buggins and Knievel jumped ‘old-school’.

The modern style saw Australians Robbie Maddison and Tyrone Gilks reach distances that were previously only ever imagined. The seemingly logical, yet primitive, straight angle take off ramp to ramp (earlier jumps were ramp to back wheel ground landings) goes against bike-jump science. Smooth curve ramp to ramp jumps follow the laws of ballistics: a powered launch, controlled unpowered flight (mid-air body movements and control tweaks influence position) and a pinpoint two wheel landing. The path is a perfect parabola from start to finish. That’s the science of motorbike jumping, and with a full understanding and more powerful bikes Maddison hammered a 106.98m world title in 2008 and Gilks a 125cc world title of 73.76m in 2009. Tragically in 2013, aged 19, Gilks was killed in an attempt to beat Maddison’s 250cc record. With the triumph of Newcastle behind him, Buggins and his Yamaha YZ250 were in top gear. He and his father, Ken, capitalised quickly on his fame and public appeal. They created the Dale Buggins Spectacular featuring fellow stunt performers Spike Cherrie, Max Aspin and later adding Dale’s sister Chantell. Touring relentlessly within Australia, Buggins and his father fine-tuned the show following the Australian Agricultural Show circuit.

With the triumph of Newcastle behind him, Buggins and his Yamaha YZ250 were in top gear. He and his father, Ken, capitalised quickly on his fame and public appeal. They created the Dale Buggins Spectacular featuring fellow stunt performers Spike Cherrie, Max Aspin and later adding Dale’s sister Chantell. Touring relentlessly within Australia, Buggins and his father fine-tuned the show following the Australian Agricultural Show circuit.

For Ken Buggins the Spectacular had two main goals. It had to be entertaining, but it had to be safe too. He couldn’t keep Dale stretching out jumps to beat world records; it was too risky. He put together a program which included moving-ute jumps, a highwire skywheel, highwire trapeze (with sister Chantell), human catherine wheel and high speed car jumps. At the Royal Easter Show in Sydney the highwire was attached to the clock tower. There was a perception of high danger, but safety measures were well in place.

Dale Buggins is part of a long and proud stunt history in Australia. Tom Gibbs managed the “fifty foot skid” for the film The Great Escape (1963). Peter Armstrong performed what many consider the greatest motorcycle stunt of all time, the “ocean dive” in the film, Stone (1974). Ian B Jamieson pulled off the spectacular Holden FX roll in the film Sunday Too Far Away, (1974). Max Aspin performed the “moat jump stunt” in Mad Max II (1981). For a Shell Oil TV commercial recreating the “barbed wire jump” from The Great Escape the task was given to Johnny “the singing cowboy” Fogwell. In 1979 live on The Mike Walsh Show, Fogwell jumped 32 cars at 176ft 10in claiming a world record. Buggins sent him a telegram of congratulations.

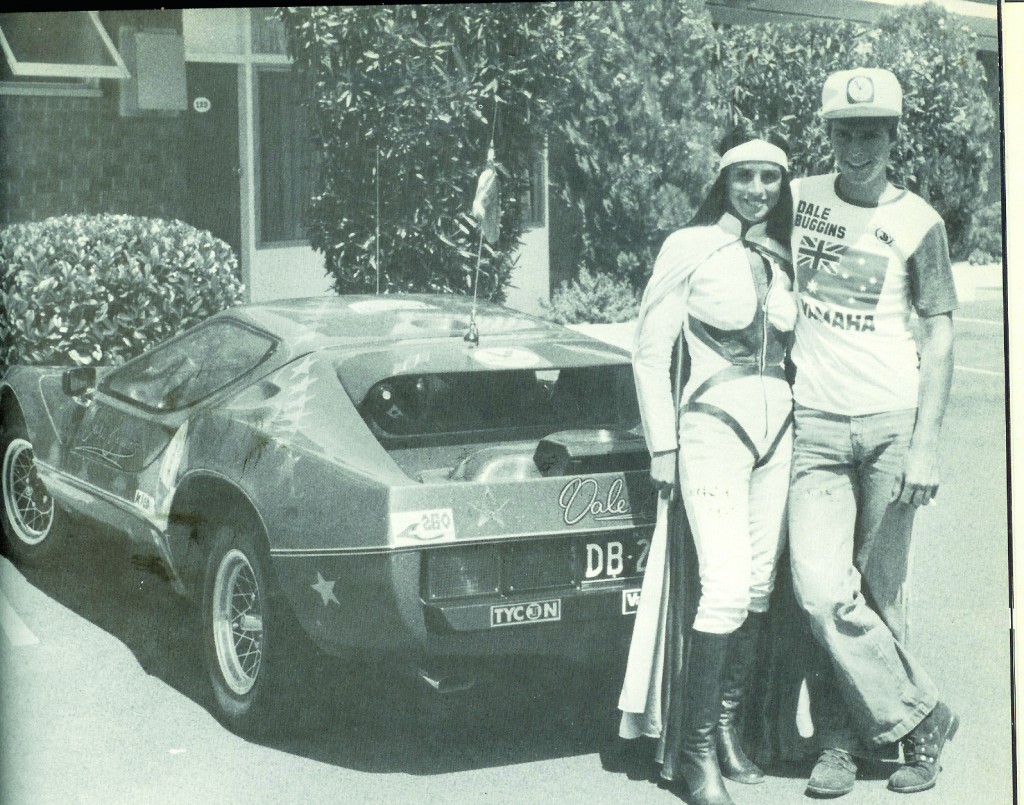

Looking back at this period in Dale’s life, it’s not hard to think he was living the dream. He was young, media friendly, good looking, well mannered and a fearless daredevil. He swapped his Purvis Eureka for a yellow Trans Am and with his flashy jumpsuit he was a hero to many. Mobbed at shows, there were articles and interviews, people knew who Buggins was and momentum to send him overseas was building. If anything was lacking it was sponsorship money. Not for want of trying Ken Buggins was at a loss to attract any significant corporate dollars.

1979 saw Buggins join The Evel Knievel Thrill Spectacular which pulled together a 50-strong stunt troupe (including Evel’s son, Robbie) set up to perform 40 shows in 9 weeks touring Australian towns and cities. Tension building between management and Knievel (in an MC role) would eventually see him abandoning the tour, but not before Buggins had, in many people’s eyes, outclassed the visitors. ’79 would also see Buggins and US stunt rider Gary Wells fight out a $150,000 long distance motorcycle challenge.

The challenge was set up as a three jump series: $40,000 for the winner of each jump and $10,000 to the loser. The jumps would build up to a 150ft mark, as this was what the American Hot Rod Association considered the “World Qualifying Gap”. The first two jumps were held in the US. Buggins won the first and Wells the second as Buggins crashed on landing, disqualifying himself. The third jump was held in Australia.

Buggins pulled out at the last minute and Johnny Fogwell stepped in. Fogwell had the longest jump, but was disqualified as the landing ramp collapsed; causing him to crash. Buggins losing his nerve was the speculation for him pulling out; however it’s more likely it was a disagreement over money owing for the first two jumps.

The greatest career opportunity for Buggins would be a tour of the United States. In the 80s success in America was considered by many, including within the film and music industries, the ultimate prize. For Dale it was no different, with the added incentive of being able to work with his idol, Evel Knievel. In 1981 he left for the US: 12 weeks, 26 shows, 14,000 miles.

By all accounts the tour did not go well. Buggins is said to have had greater expectations and along with problems being paid, an underwhelmed Buggins took it hard. He was also unable to make contact with Knievel. Knievel was in the middle of one of many trainwrecks which featured in his colourful life. He’d stopped jumping, split with his son, lost his house and many possessions due to unpaid tax and was being sued by associate Sheldon Saltman who he’d assaulted with a baseball bat. It’s a miracle he lived to the age of 69.

On September 14 Dale, his father, sister and employee Terry Blackwell returned to Sydney. In the following days they made their way to Melbourne in preparation for a show on the 19th. Many accounts put Dale in a dark place. Quiet, tired, moody, even depressed, it was not the triumphant return home he had hoped for. For those around him it seemed he was difficult to read – then particularly, but also generally.

For a boy who fearlessly catapulted a YZ250 through the jaws of danger, or death even, he was not your typical daredevil. Quiet and reserved off the bike, you get the impression he opened up honestly to few, if anyone. That to my mind is the reason he has a lasting appeal, an almost James Dean effect.

On September 18 1981, Dale Buggins took his own life in room 115 at the Marco Polo Hotel in North Melbourne. The previous day he’d purchased a Winchester model 94 Trapper rifle from a city gun shop and in the early hours shot himself in the chest. The coronial inquest determined a note found in his room had been written in his own handwriting and considering other facts subsequently ruled his death a suicide.

Since the outcome of the inquest, and still to this day, people have speculated as to why a young man who seemingly had everything would take his own life. There are many theories, but perhaps it’s best to reflect on what Dale wrote in his last note and possibly a rare insight into his true feelings.

Can’t stand the pressure. I’m so confused with life and the people in it, it’s got to the stage where I can’t think straight, too many up’s and downs…